VOICES OF KCCNYC ADOPTEES: EUN HWA’S STORY

Voices of KCCNYC Adoptees: Eun Hwa ’s Story

By Eun Hwa Han (한은화)

Knowing and Not Knowing

Photo Credit to Eun Hwa Han, on her Naturalization Day. Every Adoptee from a foreign country has to be naturalized to become a U.S. Citizen.

I was born in the late 70s, adopted by my white parents as an infant, and grew up in the south. I always knew that I was adopted. Of course, this isn’t exactly accurate, but I think what it really means is that my parents told me that I was adopted from an early age. My mother would celebrate the day in August that they flew to JFK to receive me. This date is one of many things that I would know and then “un-know” in my life. It wasn’t until I had pets and the notion of a “Gotcha Day” made me realize that perhaps I forgot the date because I didn’t want to associate with that type of objectification.

No matter how much verbal air was given to me being a “gift from God” and a part of the family (and I did feel like a true part of the family), I stood out everywhere I went. I always felt as if I just was wrong because I was so mismatched, not only from the rest of my nuclear family which included a younger brother who was my adoptive parents’ bio kid, but also from the rest of the population in my town. My high school had only two other full Asian kids and three half Asians, none being Korean. Also, back then, “Oriental*” people only apparently came in Chinese and Japanese.

*This was how I identified myself until I was shamed and educated on the inappropriateness of this term when I was in college at Yale.

Typical interchange growing up:

Q: “What are you?” or sometimes “Where are you from?”

Me: …

(I feel like this question has always gotten under my skin and I wonder how early it was that I learned what the person was really asking. I think as I got older, I would torture the questioner a bit with my silent contemplation of how I want to gratify this ignorantly posed, although clearly understood, question. I have to admit that I sadistically answered this question within the last decade as “Florida” to a fiveish year old classmate of my daughter’s.)

Q: Are you Chinese or Japanese?

A: I’m Korean.

Q (sometimes followed): Are you from the North or South?

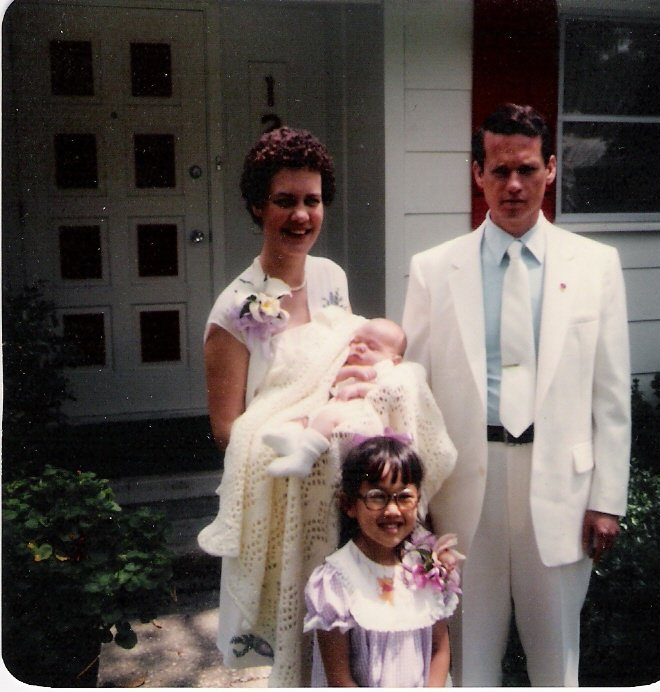

Photo Credit to Eun Hwa Han with her adoptive parents as an infant.

The facts that I knew growing up were that I was born in “Seoul, South Korea,” my birth date, that I was adopted through Holt as a baby, and that my Gotcha Day was whatever that date was in August. Ironically, my birthdate turned out to be inaccurate. I’ve since found out that I was actually born a week prior, which not only changes the birth date, but also my zodiac sign, and my lunar birth year! While I fantasized a lot consciously and unconsciously to fill in the blanks of my birth story, my adoptive parents’ attempts usually contained something about how my biological mother loved me by putting me up for adoption. I think that my parents must not have been meaningfully alluding to abortion but more the horror of being thrown into a river or something primitive like that. My mother would always state that I was her “gift from God,” an objectification that only through therapy have I realized the true depths and repercussions of her inability to see me as my own individual person, but rather as her own little China (Korean) doll. I’ve asked my parents independently why they adopted. My mother would answer how she remembered as a child seeing poor Oriental babies on TV and she told her mother that she wanted one. My father’s answer seemed to be grounded a bit more in some semblance of reason. He would talk about when he was in the Air Force during the Vietnam War, he saw that unwanted children weren’t taken in for adoption and they wanted to adopt. My mother said that they had my brother so that I would have a companion but there seemed to be some missing dots in the connection of these ideas and the actual adoption of a child by two adults who could conceive.

Back when I was born, international adoptions were less common. As forward appearing as international adoption may have seemed, my parents really had little idea what they were doing, not only as parents to non-dolls, but also sadly lacked the ideal psychological bandwidth to understand and anticipate the psychological needs that any adoptee, international or otherwise, might need. Reading Nicole Chung’s memoir, All You Can Ever Know, gave me, for the first time, the sense of being known. With her words, I was recognizing something familiar that gave me more insight into the ways of knowing myself that have been influenced by my adoption. Since we as individuals only know what we know and can have trouble differentiating what’s unique about our own experiences versus what’s universally experienced by all children, it’s taken quite a while to identify my internal narratives that are a consequence of my adoption.

Photo Credit to Eun Hwa Han with her adoptive family.

My parents’ simplistic statement that I was “their daughter,” plain and simple, without any qualifying terms is what I also blindly accepted. I understand that what they were strongly trying to convey was that they loved me and saw me as their daughter without any distinction between bio or adopted. However, what I always experienced inside was the dual realities that yes, I was their daughter, but I also had another mother somewhere else in the world. Since my mother has a pretty unsophisticated way of understanding the world and individual psychology (and a whole lot of other things as well), I saw that she would shut down if I ever challenged her or asked questions that she couldn’t answer. I remember once when I was young and couldn’t sleep because I was thinking about my adoption, I came out to talk to her about it. All I can remember from that conversation is that she used our stereo and record player to compare to the size of an atomic bomb dropped in Japan. I really have no idea what the glue was that connected that detail to my question, but all I can say is, no wonder I’ve developed a quick and strong ability to block out things that were mentally uncomfortable or just didn’t make any sense. I had to act as if I were a “normal daughter" but felt strange and different and other. Not only were my experiences unfathomable by my emotionally limited mother (my father was mostly absent at work), but they weren’t her truth and would challenge her own belief that everything was normal. And subversively, what I ended up carrying from my young years was the bullying/teasing. I was the NOT Chinese or Japanese kid, the chink, or four eyes (I had glasses from a young age too), or the facial gesture of slant eyes (image: kid pulling the corners of their eyes), or any other embodiment of my Asianness: my flat face or uncreased eyelids or thin, fine forearm hair (“What happened to your face? Why is your face so flat? Can you close your eyes? Do you shave your arms?”). Without any emotionally nuanced or patient adult able to help me hold the paradoxes of my being and my differentness, my young mind just understood myself with a reaction of, “Yep, this all confirms that I’m wrong.”

And while my different outside always seemed up for open discussion and critique, my insides were also quite different. Something that my parents did realize was that I was very smart. I was tested at a young age and skipped kindergarten. Even as the youngest in the class all through high school, I was usually the smartest in the class. Of course, this difference also was held in my mind with embarrassment and shame as another thing to try to hide. I also believe that I had some sense of the model minority stereotype back then, which also made my intellect and math skills even more a betrayal of my Asian “otherness”.

Photo Credit to Eun Hwa Han

I still rankle when being treated in a way that feels informed by Asian stereotypes: that I must be a passive, quiet, compliant, unassuming, or subservient person. Ironically, any of those traits that I may demonstrate have nothing to do with my Asianness but my Caucasian parents' upbringing of me. My parents were ill equipped to handle my ability to question things and I now realize that as a survival mechanism, many of my uncertainties about myself and my adoption went deeply underground to keep the equilibrium of my parents’ “there’s nothing to see here, everything is completely normal” way of life. Things, according to my parents’ unspoken rules or lack of abilities, weren’t to be discussed or processed or acknowledged to have nuance, but they were very black and white, and if in doubt, pray and pray that your prayers are answered (me: Huh? I’m not sure how that will solve my real problems…) I became quiet at home as I realized the great distance between them and I. I remember in high school, having the realization that I had to work hard to become successful and make money to avoid the life that they had which was full of stress and arguments about money.

My mother was very controlling and religious and my father spent most of his time at work but was terrible with money. We grew up financially strained, but my mother’s strong work ethic and miserliness helped us get by. I left to go to college in the Northeast on heavy financial aid and little knowledge of what college was all about, being a first gen college student. It was difficult to go from my small town high school, where grades were a breeze, to Yale where everyone seemed smarter, more interesting, more sophisticated, and with more money. I took as many classes as I could and worked at work study jobs, as many hours as allowed. When my father threatened to not pay the family’s small expected contribution of the tuition for my freshman spring semester because I wouldn’t allow him to send my report card to the town newspaper, I had the school bursar change the billing address to my school address and essentially became financially independent at the age of 17. (Because I had skipped kindergarten, I turned 18 during my freshman year of college.) Besides gifts for birthdays or Christmas, I haven’t received any money from my parents since then. I moved off campus for my sophomore year, continued to take as many classes and work as much as I could and finished my coursework in three and a half years so I could work full time that last semester. I took the MCAT the day of my maternal grandmother’s funeral because the family wouldn’t change the day and I luckily still got into medical school. This was especially sad because she was my beloved grandparent, who was a generous, fairy godmother grandmother to us when I was growing up. She was widowed and had remarried someone with money and would buy things for us, but I wish my mother would have asked her for more help when we were growing up. I wasn’t allowed to do any extracurriculars because everything cost too much money, e.g., the special tennis shoes for the sports teams, the musical instrument, etc.

Photo Credit to Eun Hwa Han.

In medical school, I found my people. I had a number of Asian friends and there were other commonalities that helped me to find myself a bit more in those early years of independence. In residency, I also felt an easing up living in the ethnic melting pot of NYC. I met my husband, got married, had a child, moved to the suburbs, had a second child, and have had a good life. The birth of my first child was an especially poignant and meaningful moment. He was the first known “blood of my blood” and I felt a significance to the word “family” that I hadn’t ever known before.

Late 2010s

It took a 40 year old midlife crisis to finally enter into therapy and only then did I begin to unwrap the complicated layers of compartmentalization that had preserved me in my home and southern Christian community. Along the therapeutic journey, I allowed myself to acknowledge that I was adopted and this was a trauma that was difficult to process. My acknowledgement and even fantasies about a Korean mother could begin to be gently explored. I didn’t really, ever envision a father in early secret ponderings of my Korean origins. With all of my complex Jenga-like compartmentalizations, this really meant just letting some realities more fluidly into my consciousness that I had unconsciously ignored to be able to survive. With all my “giftedness” (my mother used this word frequently but I always felt that special = freak), I was also very gifted with knowing and unknowing simultaneously. Allowing myself to only verbalize in therapy some of the curiosities about my adoption and acknowledging that my adoption was a preverbal complex trauma was completely uncharted territory. I had to un-know much in my life to be able to tolerate my childhood and get along with my mother. While I now understand that for any adoptee, desiring something, whether it be knowledge or more of a birth family, could feel like a betrayal, with my mother, I do believe that it would truly be that.

Photo Credit to Eun Hwa Han, with her biological family members

Despite being a physician and knowing that genetic testing was easily accessible and could reunite adopted children with their biological parents, I nervously bought 23andMe with the conscious goal to find out if I had any BRCA genes for breast cancer. The results found that, thank goodness, I did not carry any risky genes but also there was someone estimated to be a second cousin given the percent of overlapping chromosomal commonalities. I even more nervously contacted him and found out that he was a Korean living in Canada, studying nursing, with excellent English skills. He had a different family name from mine. While we thought that his father and my mother may have been cousins, he still asked his father if anyone knew of any adoptions and we reached a dead end. He, of his own motivation and eagerness to help me find more information (and to my horror, as he so earnestly took up my quest), called the Holt adoption agency and shared with me that I could request my full releasable record. His problem solving approaches were a stark contrast to my anxious passiveness about my biological family and really spotlighted how ambivalent I was of rocking the boat of my internal mental Jenga. I had a husband, a house, two young children, a private practice, and my general style with anything is cautious and thoughtful and conflict averse. I hesitantly, yet quickly, mailed the form necessary to request my record and received an email with that information. Amongst other details, I learned that my parents had met through a friend of my birth mother’s and she was 18 when I was born and had to put me up for adoption because they were unmarried and my father had to leave to serve in the Army. I also learned that I could request an “Assisted Search” into my bio family. To my understanding, Holt would attempt to contact them and if they were found and agreed as well, we could be connected. I only had to fill out a form and write an introductory letter. That 2019 email detailing this process is still flagged in the bottom of my email inbox. I wasn’t able to write that letter. I had no idea what to say so I put it out of my mind and basically “forgot.”

My birthday seemed to become more and more complicated as I aged, but was always associated with wistfulness, wondering if my birth mother also thought about me on that day as I would about her. My lack of a birth story was something that always had made me sad and was a small drop that could trigger a flood of impossible fantasizing and ponderings. I believe that there must be a number of these little interconnected associations that I hold because as buttoned up as I like to be, I ugly cry all the time during the most unassuming scenes in books and movies. The birthday emotions were more noticeable as I aged, with the worry that if I were to wait too long to try to make contact, perhaps my birth mother would die before I could.

December 2022.

One pre-Christmas, December morning, I groggily was glancing through my emails and noticed a notification email that I had a message on 23andMe:

A relative has sent you a message:

“Hey! I just saw you on the family relative list and I’m curious which grandparents we might be sharing.”

I jumped up from bed and ran to the bathroom to open the message on the website to see the full message from someone with the last name Han.

I replied:

“Hi,

I think it could be possible that our fathers were brothers. I was given up for adoption to an international agency as an infant, but was born in Seoul in 77 and given the name Han Eunhwa. I know that this info could be a shock to you and your family but any info you might be able to share would be welcome.

Thanks”

Looking back, I’m a little shocked at the succinct little bomb that I dropped in my reply. The messages continued back and forth between my Korean cousin living in the midwest US, her older sister, also in the US, her mother in Korea, who actually knew of my adoption, and, yes, my mother (!) and my sister (!!) in Korea. Over the next few days leading up to Christmas, I had a video call via Kakao Talk with those cousins and my mother and sister. I messaged with another sister and brother. I found out that my mother had left her abusive family home in her teens after her mother had died and her father had remarried. She met my birth father through a friend that she worked with. They were unmarried and young and his family was poor when she became pregnant with me so she was pushed into putting me up for adoption by my father’s older sisters. They stayed together and had another girl two years later, married, and had another girl and then a boy. They divorced later when the children were older.

Photo Credit to Eun Hwa Han with her biological mother and siblings in Korea.

Christmas 2022 was filled with happiness for me. I was euphoric. It felt like the hole in my identity and my heart was finally filled. Just knowing the story was so helpful, like the feeling of completeness after having found some missing pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, but that the story was also a good one filled me with such overflowing joy. To find out that I came from a family of love, that my parents loved each other and I was a product of that and that they stayed together even after giving me up and had a family together was quite special and meaningful to me. Coming from a family of love was even more significant because my adoptive parents were quite unhappy with each other when they were together and it was a relief when they finally divorced.

I planned a trip in the spring for a long weekend and met my cousins who were close to my nuclear family when they lived in Korea. I was amazed to hear their own stories of immigration to the US from Korea and admired and recognized their strength and resilience. I also developed an appreciation of the curve balls and unknown trade offs that life can bring. I recognized that while I had seen my younger years as emotionally and financially difficult, theirs were as well. While I missed out on the connection of growing up as a part of big family in my home country, I also had privileges of American citizenship that I had taken for granted.

I began learning Korean on apps like Duolingo, Rosetta Stone, and LingoDeer in preparation for a trip to Korea in August 2023 with my children. I was apprehensive about the trip and mentally prepared myself with low expectations, so that I wouldn’t be disappointed. The trip was glorious. They had taken such care to plan our time there and make us feel welcome. They were wonderful, kind, considerate, funny, and I felt an easy comfort - like I finally was home. My children also had similar experiences and enjoyed being part of a big, close, easy going family.

There was a moment in Korea when I was watching and smiling at a young child’s antics with his parents. When he looked at me, I furtively looked away and became self conscious. It was then that I realized that I had developed this reaction after being gawked at by American kids because I look different but being in Korea, I don’t stand out at all. This otherness has been felt all of my life. I remember comparing my experience to the few other Asian kids that I knew and feeling so alone because they at least had their family that they optically matched.

Photo Credit to Eun Hwa Han with her children, and her biological father.

There was another experience on my third trip to Korea when I was watching the easy closeness and conversation between my sister and mother and felt a bit of sadness, wishing that I could have that also, with either of my mothers. The line of a song came into my mind “I will always feel strange inside, I will always feel…?” I had to Google it and, don’t judge, it was Everclear’s Father of Mine. I got all teary reading the lyrics to that 90s grunge song and had to quickly clear my mind so as not to distress anyone there with my tears. Much later on when I “remembered” and processed this moment in therapy (knowing and unknowing doesn’t go away that easily), it was a bit shocking to see how the moment brought to my mind a little clip of a song that so aptly connected to my hodgepodge of feelings. I’m pretty sure that I never made that connection listening to the song in the 90s or up until that moment. The song (full lyrics below) speaks about an abandoning parent and a naming parent. There’s also an idealized parent and an idealized child. There’s a child who feels scared and is a minority in their neighborhood. A child who will “never be safe, never be sane, always be weird inside, and always be lame”.

After sharing with my adoptive father that I had reunited with my birth family, he was happy for me and shared a story with me that I had never heard. He told me how I cried for the first two weeks that I was in the US. He imagined that everything must have been so strange to me - different faces, different sounds of language, different arms from the foster mother who raised me those first six months, different milk, etc. I realized that my adoptive mother had likely kept me from a relationship with him during my younger years. Although he can still be a difficult person, our relationship has become less strained over the years. I still have not told my adoptive mother about the discovery and reunion with my Korean family. Both my brother and father agree with my initial inclination that she wouldn’t be able to handle it. Our current tenuous relationship wouldn’t be able to handle the predicted upset and betrayed feelings that she would likely experience. As she already has a tendency to cut ties with her own siblings for years at a time, we imagine that she could do the same with me if she were to be aware of my happy reunion with my birth family when my relationship with her is quite difficult.

Photo Credit to Eun Hwa Han. Her biological nephews and nieces with her children.

While I was still in Korea, I looked up Korean classes and messaged KCCNYC so that I could really learn Korean to be able to speak to these new people that I so desperately wanted to connect with and know. I’ve now been taking Korean classes for over a year, have traveled to Korea three times with my children, and am hopeful and excited about the growing connections that I’m making with my mother and siblings and birth country. I’ve met my father also who shared with me that he went twice to Holt when the family was better situated to attempt to find me. I realize that if I had sent that introduction letter and form when I first received that email, then Holt may have seen that they were open to contacting me and the reunion might have happened a few years earlier. I also found out that that Canadian second cousin is actually a first cousin. My birth mother and his father are siblings but they didn’t know about me. As everyone important is still alive, I don’t regret not sending that email earlier as I feel that everything has had a time and process. I have also been slowly finding my way back to them and feel strong and grounded and ready for the next chapters in my life. With my birth family, even though we don’t speak the same languages, and there are the obvious difficulties that can come in any relationship, I feel a sense of peace and wholeness in knowing them.

Father of Mine by Everclear

Father of mine

Tell me, where have you been?

You know I just closed my eyes

My whole world disappeared

Father of mine

Take me back to the day

Yeah, when I was still your golden boy

Back before you went away

I remember blue skies, walking the block

I loved it when you held me high, I loved to hear you talk

You would take me to the movie

You would take me to the beach

Take me to a place inside that is so hard to reach

Oh, father of mine

Tell me, where did you go?

Yeah, you had the world inside your hand

But you did not seem to know

Father of mine

Tell me, what do you see?

When you look back at your wasted life

And you don't see me

I was ten years old doin' all that I could

Wasn't easy for me to be a scared white boy in a black neighborhood

Sometimes you would send me a birthday card with a five dollar bill

Yeah, I never understood you then and I guess I never will

Daddy gave me a name

My daddy gave me a name

(Then he walked away) daddy gave me a name

(Then he walked away) my daddy gave me a name

Yeah

Oh yeah

Yeah

Daddy gave me a name

Daddy gave me a name

(Then he walked away) daddy gave me a name

(Then he walked away) my daddy gave me a name

Yeah

Yeah

Oh yeah

Father of mine

Tell me, where have you been?

Yeah, I just closed my eyes

And the world disappeared

Father of mine

Tell me, how do you sleep?

With the children you abandoned

And the wife I saw you beat

I will never be safe

I will never be sane

I will always be weird inside

I will always be lame

Now I'm a grown man

With a child of my own

And I swear, I'm not gonna let her know

All the pain I have known

daddy gave me a name

(Then he walked away) my daddy gave me a name

(Then he walked away) my daddy gave me a name

(Then he walked away) my daddy gave me a name

(Then he walked away) yeah

(Then he walked away) yeah

(Then he walked away) oh yeah